Engage students in a structured academic controversy, in which they look at multiple viewpoints around the question “Should we celebrate Columbus Day?” The goal isn’t to win a debate, but to articulate both sides of the question and form a conclusion based on the critical analysis of evidence.And it’s fundamentally important that they do so. Students need to grapple with these multiple perspectives in history and the not-so-pleasant aspects of our past. We don’t want to expose young kids to graphic accounts of brutal treatment of Native Americans, but I think you want them to begin to question: What did this person do? Why is he important? Why are we celebrating him? How could we look at this from a different perspective?īased on my experience, I think it’s vitally essential that teachers engage kids as young as sixth grade in questions that really interrogate Columbus. Teaching Columbus accurately and age-appropriately: Turning points are powerful lenses through which students need to view our past. Why we should still teach Columbus:Ĭolumbus did not “discover America,” but his voyages began the Columbian exchange, a turning point in world history involving the massive transfers of human populations, cultures, ideas, animals, plants, and diseases. If we have a holiday honoring somebody, the question on everyone’s mind should be, “Why are we honoring them? What were his actual contributions?” Those are important questions we want to ask as citizens. Historical knowledge can help students create an argument to answer those questions.Īnd in general, we want to students to engage with controversy. Right now, across the country, cities and schools are faced with the question, “Should we celebrate Columbus?” We’re facing similar questions about how we commemorate the confederacy and the Civil War. The Columbus controversy can also help students see that history is still applicable today. And those multiple viewpoints may help engage students who might feel otherwise unrepresented in a history class, such as females and students of color. It involves grappling with multiple perspectives, a fundamental skill for historians.Dominant narratives tend to speak about heroes in a simple sense counternarratives can be much more critical. It requires looking at dominant narratives and counternarratives.It involves really unpacking the past, looking for complications, and making a deep exploration into the people that made history happen, rather than just looking for a glossy overview.Understanding controversies - what Columbus did, how he did it, whether we should be commemorating him - builds skills that are fundamental for understanding history and social studies.

Why the Columbus controversy matters for students: We need students to understand that Columbus is important, even if he isn’t someone to be celebrated. Some of my students entered high school aware of the problematic nature of Columbus - but their thinking is, “Well, Columbus is not important to study, because he didn’t do anything.” We have to push back on that.

I think that’s part of a larger push nationwide to be critical of our past. Some schools, cities, and institutions, such as the Harvard Graduate School of Education, have adopted Indigenous Peoples’ Day instead. There’s definitely a trend toward questioning Columbus Day.

Trends are really hard to detect in a country as divided as ours, but I’ve noticed two developments in my work teaching high school and teaching at Harvard. We asked Eric Shed, a veteran history teacher who now directs the Harvard Teacher Fellows Program, to share perspectives on the changing currents around Columbus Day and the challenges of learning and teaching history, as distinct from celebrating it. Just as the country grapples with the meaning and problems of Confederate monuments, so too are schools, towns, and even whole states grappling with “Columbus Day.” Many are deciding to rename and refocus the holiday, choosing to call it Indigenous Peoples' Day to honor the people whose lives and cultures were irreparably damaged by the colonial conquest that the age of exploration ushered into being.

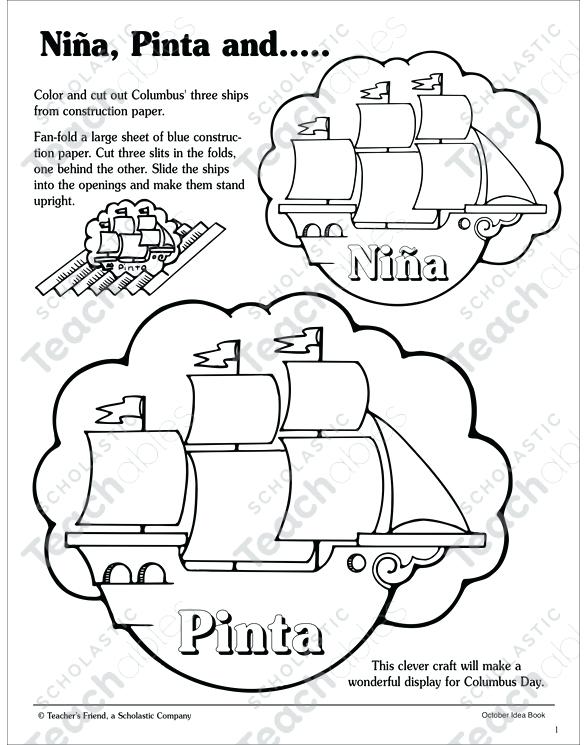

In recent years, the conversation has become more nuanced, as educators - and people across the country - have begun to explore the many reasons why celebrating Christopher Columbus is problematic: the violent abuse of indigenous peoples, the launch of the transatlantic slave trade, and the introduction of a swath of lethal diseases to an unprepared continent. If the commemorations dealt at all with the impact of European exploration on the indigenous civilizations already flourishing in these “discovered” lands, it was often fleeting. Once upon a time, teachers celebrated Columbus Day by leading children in choruses of song about the Nina, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)